Part 1: When Seeing Isn’t Always Believing: Images in the Era of Fake News

This is Part 1 of a 2 part series exploring the context of constructed images and our perceptions through the media

In 1829, Sir Robert Peel developed the 9 Principles of Law Enforcement. He is considered the father of modern policing in western Europe and the U.S. The principles were given to British law enforcement officers as general instructions. The second principle stated: The ability of the police to perform their duties is dependent upon public approval of police existence, actions, behavior and the ability of the police to secure and maintain public respect.

Flashing forward to 2015, the Justice Department under President Obama, awarded grants for over $20 million to 73 local agencies in 32 states to expand the purchase and use of body-worn cameras. The goal was to build trust and transparency between law enforcement and communities of color especially after several high profile deaths of unarmed Black men.

Perceptions are important in policing. As a civil authority, citizens must believe they can trust them. When this breaks down, distrust simmers and can fester into resentment. This can happen on both sides. Perception is one way that we interpret reality and if we perceive it to be a threat (police officer or a citizen), we will fight or flight.

Perceiving something is not simply to assign meaning in our mind to what we see and hear. It can also mean adapting our life to a new reality.

I wrote a commentary earlier this year asking Do We Live in an Image Culture? I showed the limitations of image as a communications tool compared to speech and written language. Although both language, speech and images can be manipulated, we tend to think that only the latter can be used as objective evidence.

Let me start with this question.

Did fake news start with image manipulation methods and software? Or did it start with our propensity to lie?

The Big Lie

The Big Lie

Conventional wisdom says there are always two sides to a story. Our legal system is built around this idea and gives it weight by declaring that the accused is innocent until proven guilty. Every American citizen is entitled to due process according to the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

Five years ago, I was called for jury duty in Philadelphia. This process always scared me. I promised myself as a kid that I would stay away from law enforcement agencies because I grew up with a real fear of the criminal justice system. During the trial, a young adult Black male was being accused of shooting his enemy’s girlfriend ten times. The jury had to sit and hear the testimonies of the victim and the accused. Keep in mind that when the jury met to deliberate, we had to decide if the accused was guilty based on the evidence. The burden of proof is high when one starts from the presumption of innocence. The hardest part was, after the trial was over, I knew in my mind he was guilty. But it could not be proven beyond reasonable doubt. As a result, this man walked free.

Was justice served?

We tell ourselves that if there is enough overwhelming evidence, the truth will prevail. Well, in an image driven society, this approach is fraught with problems. Although our brain is like a super computer, it was not designed to process hundreds of images simultaneously. As a matter of fact, this is a new phenomenon in the history of humankind driven by electronic technology. This means our brain must decide what to focus on and what to ignore. This is called inattentional blindness. (This is why multi-tasking is a myth.)

If our brain blocks out an image that shows a grievous wrong, does this imply our complicity? Is our brain ignoring the truth? Facebook is rife with causes bold enough to pronounce judgement on you if you do not respond to their call to action. One post said non-responders are heartless. Another said you will forfeit God’s blessing. Showing arresting images and pressuring the viewer may prick someone’s conscience. Sharing it may even make one feel better or worse but it may not change the underlying issue of why the image was posted in the first place.

Why?

The big lie we promote is that seeing is believing. A premium is placed on our senses which helps us to understand the material world. This implies that we hold some kind of magical ability to always understand the truth through our senses. Compounding this issue is our pluralistic society’s relativistic view of truth. Without objective truth standards, any image, speech or written language can be re-interpreted which can make a mockery of justice and fairness. Whoever has more money and influence will have the power to manipulate the truth and the images that go with it. And let’s be honest, this has happened a lot in the last 30 years through soundbites and professionally doctored images. (Even the tabloids have gotten better at presenting doctored photos as true. smh)

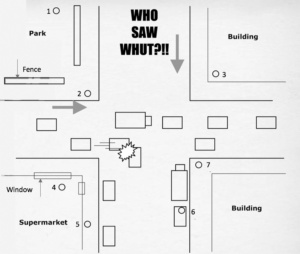

Viewpoint diversity is possible (see diagram below) but that is no excuse to abandon the pursuit of Truth. In their book Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture, Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright refers to a concept called The Myth of Photographic Truth:

…when a photograph is introduced as documentary evidence in a courtroom, it is often presented as if it were incontrovertible proof that an event took place in a particular way. As such, it is perceived to speak the truth. At the same time, the truth-value of photography has been the focus of many debates, in contexts such as courtrooms, about the different “truths” that images can tell.

In short, if images are socially constructed artifacts, context matters. That means your context may determine how you interpret the photo.

Take a look at the diagram above. This is a simulated car accident scene at an intersection. The small rectangles are vehicles and the circles are people. Each person viewing the accident has a POV. I used this diagram while teaching a Cross Cultural Studies class at Eastern University. The students could only ask me yes or no questions. Here are some of them:

- Is person #4 on the 1st floor?

- Did person #3 hear the accident?

- Could person #5 see the accident when there is a parked car obstructing the view?

- Could person #6 see sitting behind a truck? If not, did they hear the accident?

- Is the fence tall enough to obstruct the view person #1?

- Based on their position, which person’s POV are you more likely to trust? Does this change depending on the person’s character?

Part 2: 5 examples of how an image is perceived differently from its reality.