Networking for the Rest of Us: Building Social Capital

I was shocked when I found out two important pieces of knowledge in the past 5 years: most successful entrepreneurs come from wealth and that the average entrepreneur is at least 40 years of age. I now realize that I have been paying attention to the wrong people.

Everyone knows that the best way to grow your business is through networking. Businesses don’t grow by themselves. Building a sustainable network to support your business implies access or getting access. But access to what?

Social Capital.

While in grad school, I read several books about this subject. According to Nan Lin’s book Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action, his definition of social capital is the investment in social relations with expected returns in the marketplace.

Entrepreneurs from wealthy backgrounds have social capital baked into their social relations courtesy of their family ties. In short, money talks. Think about it, wouldn’t risk tolerance be more desirable if there was a safety net? For the rest of us, one mistake means our business could be gone like the wind. Boot-strapped entrepreneurs don’t always get second and third chances.

In addition, how does one access social capital when your upbringing is filled with dysfunctional relationships?

My Story

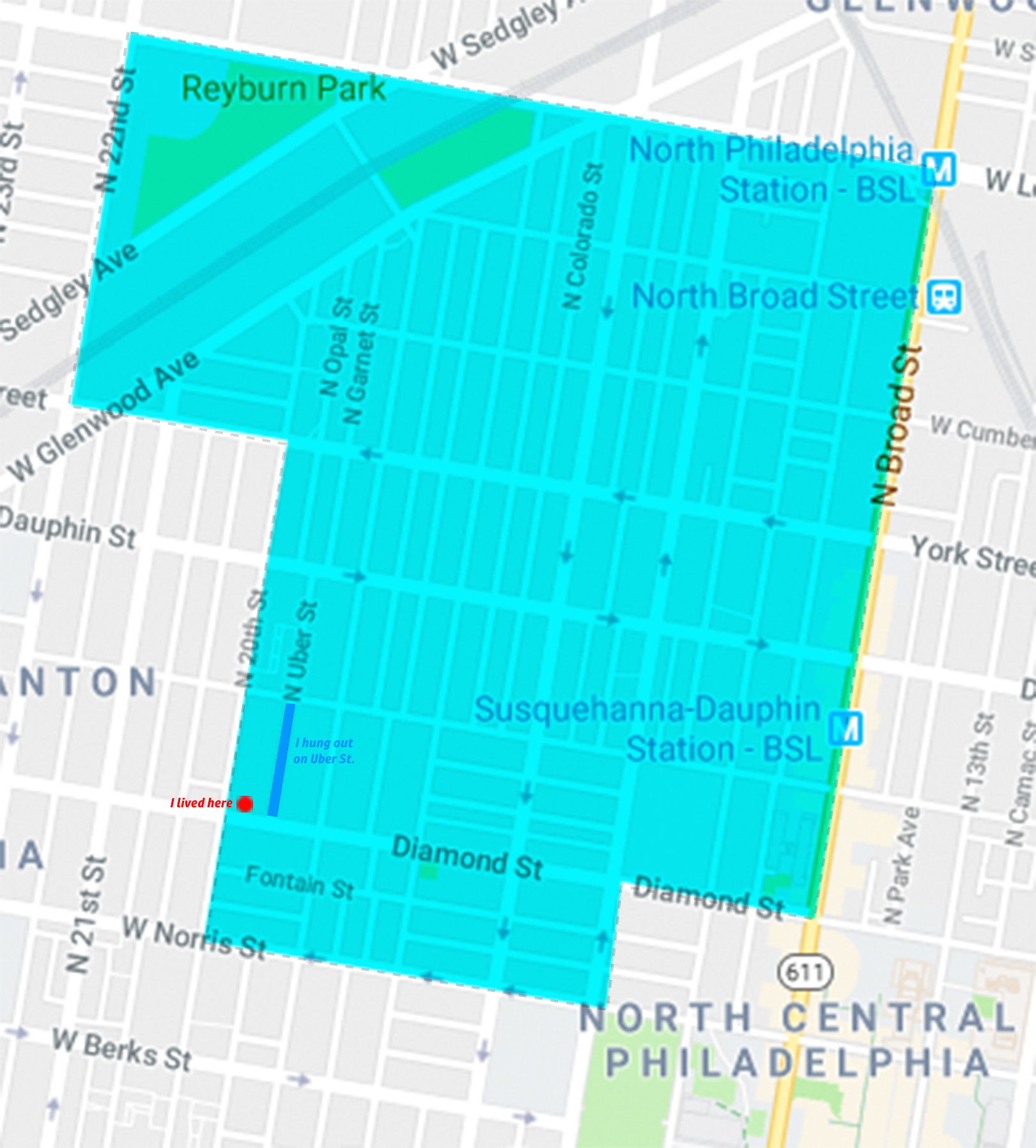

North Philadelphia (above) is where I grew up. I restricted my exploration to the blue perimeter on the map. The red dot is where I lived and the dark blue strip is the street where I spent most of my life until high school. My only safety net was learning to run, fighting, riding my bike or traveling with friends. Commercial areas functioned as neutral zones. Based on the map, it is pretty clear where the boundaries of my social capital ended. To travel outside of the perimeter was always a risk.

The risk got real when I had to travel to a white working class neighborhood to attend a magnet middle school. For two years, white adult men and their sons threatened all of the black male students telling us not to be in their neighborhood after 3pm. In one instance, I stayed after school for a project and lost track of time. A white friend told me not to walk to the Elevated train stop near the school. This was a gathering place for local high school kids and it was also near the bars their fathers frequented. Instead, he secretly escorted me through back alleys to catch the train at a different stop. It took 30 minutes and I was scared as hell. Briefly, I entertained the notion that he was leading me into a trap. I made it safely to the train. I was thankful for that friendship. (I obviously had some form of social capital with my white friend.) But that experience affected my perceptions of white men for at least 20 years. No amount of social capital protected me from being chased, bit by a dog and taunted by old white men in this neighborhood. I vowed to never go into this type of neighborhood in the future. Sounds like 1950? This was the early 1980s.

This horrible experience taught me something: social capital has its limits. There are spaces where I have to trust my instincts or I will need allies. By and large, white men will never know this experience. As I got older, I enlarged my perimeter. However, because of my middle school experience, I still attended a high school within the blue perimeter. (Even today, I am careful about my children attending schools in white working-class neighborhoods.)

During my high school years, my brothers and cousins were amassing tremendous social capital all over North Philadelphia playing in PAL (Police Athletic League) basketball leagues. When all else failed, I invoked my family’s last name and mentioned the word ‘basketball’ to occasionally negotiate safe passage outside the dotted lines.

The marketplace in my community was an interesting one. Everyone was on their grind and had something to sell. It might be out of their car (clothes), in front of their house (auto mechanic), out of their house (chicken dinners) or the corner store. I look back on the 1970s and marvel at how poor and working-class Black people found ways to be entrepreneurial.

But in the 1980s, the social capital necessary for these pop-up businesses became anemic. Family and community disintegration, crack addicts, unsympathetic law enforcement and a social welfare system that encouraged dependency began to sap the creative spirit in the community. In addition, Asian merchants set up shop with their own social and economic capital that came from their own communities.

Once I entered college, my social capital changed overnight. Most of the people in my community were poor Black and working-class people. In college, I was sitting next to mostly white students who graduated from private schools and wealthy international students. Here I am in the middle of this college environment trying to figure out how to function. Bad memories from my middle school years still haunted me. It eventually became clear to me that nothing from my background was of value in this space. Very few people asked about my community, my experiences or artistic talent and knew that I was putting myself through school. This realization brought on a form of culture shock that lasted the whole time I was in college even though I was in Philadelphia! Even after I graduated, it took me a while to see myself as a trained professional.

My Experience

Here are the standard nodes (actors) within a larger network where social capital is built:

- Family and/or friends

- Grade school (teachers, parents, etc)

- Higher education (professors, students, etc)

- Clubs/Organizations (fraternal, associations, etc)

- Events (networking, training, political, industry, etc)

- Professional (job, etc)

There are resources embedded in each of these nodes. If you grow up in a middle-class family, you may have access to at least 4 out of the 6 nodes. That’s pretty good. But when you grow up poor, you might have access to 1 or 2 IF you are lucky. If you receive no education, there is a strong chance you may have access to 1 node (family and/or friends) and may add your own informal ones. How many of these nodes did you have access as a kid? In college? In the professional world? Some believe lack of access to social capital is always circumstantial. Well my previous experience in middle school says it is not.

Here is an example I experienced in my young professional years.

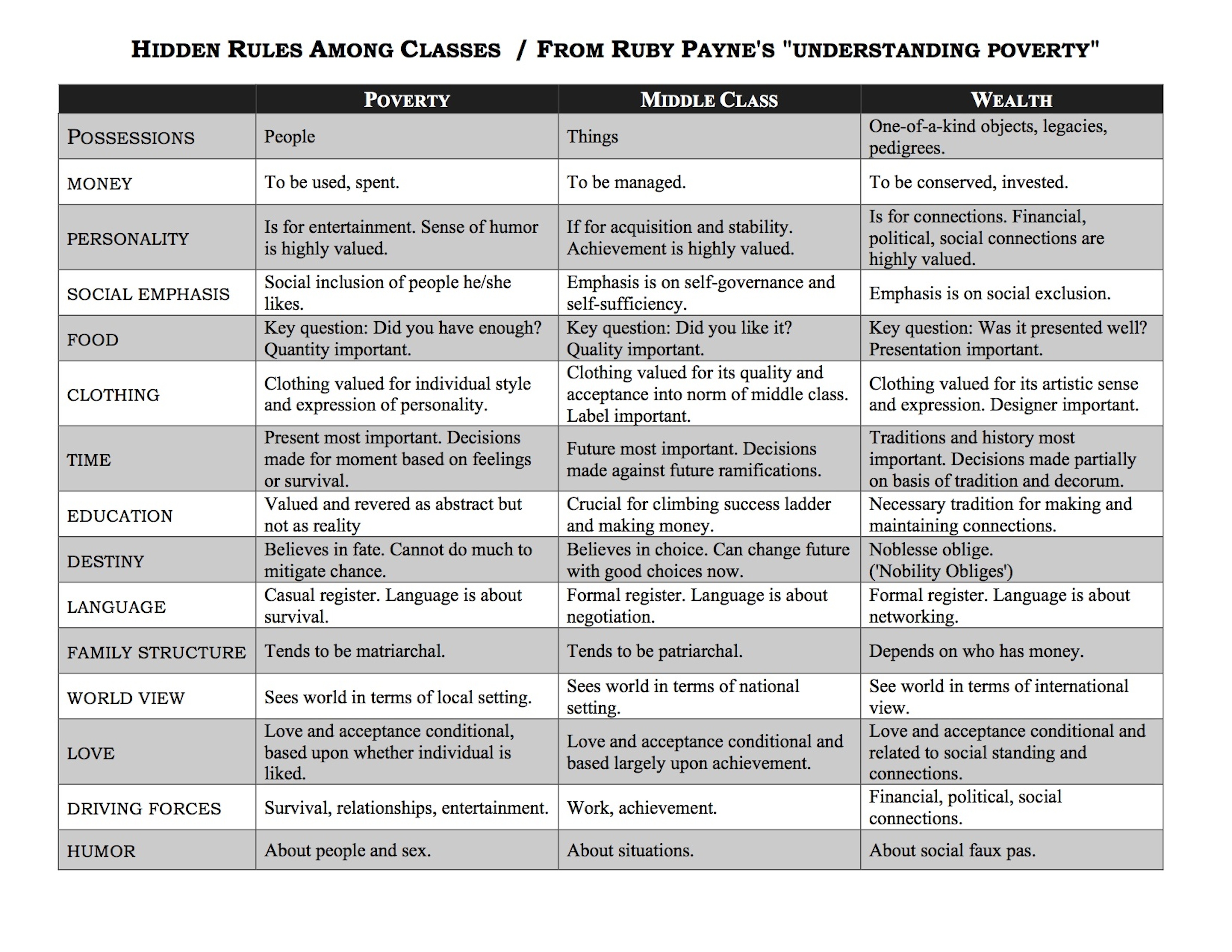

As a professional graphic designer with a degree, my employer allowed me to purchase an AIGA membership. AIGA is my industry’s volunteer trade association. Membership allows access to networking events, a jobs bank, etc. However, at events, I was ignored. This became a consistent pattern as I tried to get to know others. To make things worse, every time I showed my membership card at events, I was questioned extensively as if I was lying about being a member. Was my experience circumstantial or discriminatory? The hidden rules and the elitist attitude eventually discouraged me and I discontinued my membership. Ruby Payne’s chart speaks to some of this issue.

Do you know how difficult it is to move between classes? In my younger professional years, I quietly struggled with Imposter Syndrome every time I attended an AIGA event. It takes a special person to function inside networks that don’t value you. Occasionally these kinds of spaces will reach out because you have something that they want. Today, my approach is to I let them feel a blast of my superpower but not to give them access to my cape. I place my energies in spaces that do not fetishize me.

Do you know how difficult it is to move between classes? In my younger professional years, I quietly struggled with Imposter Syndrome every time I attended an AIGA event. It takes a special person to function inside networks that don’t value you. Occasionally these kinds of spaces will reach out because you have something that they want. Today, my approach is to I let them feel a blast of my superpower but not to give them access to my cape. I place my energies in spaces that do not fetishize me.

My Network

Here are 5 nodes in my network that I have found helpful for my personal and professional growth:

1. Faith/Religion: As a pre-teen, I saw Christians of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds from a local church move into my neighborhood when everyone else was fleeing. Their commitment to Jesus’ example led them to make sure I had a place to stay and that I graduated from college. My in-laws are some of these people. They raised their daughters in North Philly and still live there. Their example along with others gave me a foundation for caring for the less fortunate. Today, I am involved in a multi-ethnic church in NE Philly that does significant community work in a diverse ethnic, cultural and religious community.

2. Community Development: I am connected to Community Development Corporations (CDCs) and community nonprofits. Many of them are faith based providing training, services and education in marginalized communities. This is one of the few spaces where I have found people (with and without education) willing to share resources and with high social impact convictions.

3. Higher Education: Since receiving a graduate degree, I stay connected to my professors and some of my colleagues. Because of them, I am able to stay abreast on the latest ideas and research in the social sciences that impact graphic design. (Unfortunately, I cannot say this about my undergrad years. They were very contentious.)

4. Education (Grade School): Part of my career involved being a youthworker inside grade schools and occasionally teaching subjects. I got to know principals and teachers as friends.

5. Friendships: I have friends in every socio-economic class (including wealthy people). This is intentional because I don’t want to lose contact with my low income/working class roots. This keeps me humble and generous and allows me to pay it forward from time to time.

As a result, my design work leans toward businesses and nonprofit organizations interested in these areas. I am thankful that my network is very diverse and multicultural.

There is one trait I have consistently found in each of these nodes: altruism. I am delighted to meet people who are not chasing money (although they may be doing well with it) as their sole purpose in life. Their guiding principle is to help others and their generosity is evidence of that. These same people will call me when my design and strategic thinking talents are needed and will quickly recommend me to others. They are people I like to work with and people I would hang out with.

I avoid networks that are selfish, elitist and encourage unhealthy competition. There are a few that I am trying to repair from my past. There are others where I have been gone too long to benefit from them. In both of these cases, I have committed to being a discerning giver when opportunities present themselves and not to expect anything in return.

Although my biological family node did not always function right, there is one thing I embrace from it: grit. Angela Duckworth, professor of psychology at University of Pennsylvania and author of Grit: The Power and Passion of Perseverance, defines it as “passion and perseverance for very long-term goals.” She asserts that those with grit are able to work through failures, persisting in their fields until success is reached.

In conclusion, I admit that I never thought my network was extensive enough to attract interesting projects. But once I started working for myself and talking to people within my nodes, I saw my network even more clearly. The truth is, my resilience was forged by my mother. My bad experiences impacted me but did not break me. But my social capital was built from the social capital of others stepping into my life.

This is why consider myself successful when I can use my social capital to help others succeed. And guess what? Even though I have been mentoring youth for over 25 years, I started my business when I was over 40 years old.

What do you think?